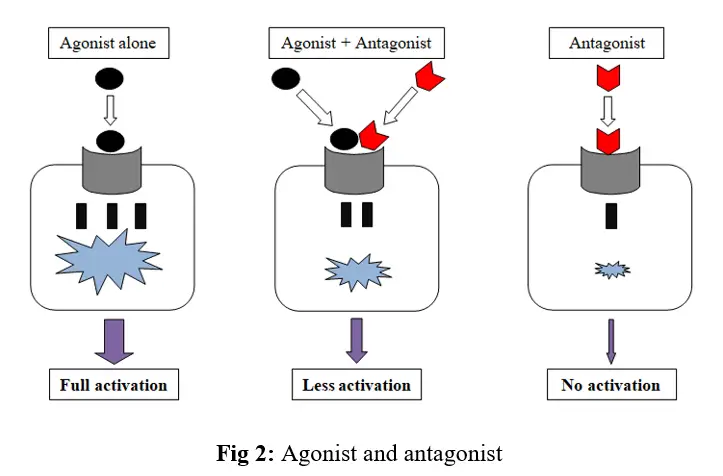

An agonist and an antagonist are two types of molecules that interact with receptors in the body, but they have opposite effects on the receptor and its downstream signaling pathways.

Agonists:

An agonist is a chemical that bind to a receptor and activates the receptor to produce a biological response. For example, Heroin, methadone, morphine etc.

- Binding and Activation: Agonists are molecules that bind to a receptor and induce a biological response by activating the receptor. They typically have structural similarities to endogenous ligands and bind to the receptor’s active site, triggering a conformational change in the receptor protein.

- Types of Agonists:

- Full Agonists: These agonists fully activate the receptor, leading to maximal biological response.

- Partial Agonists: Partial agonists activate the receptor but produce submaximal responses compared to full agonists. They may also act as antagonists in the presence of full agonists.

- Superagonists: Superagonists are agonists with increased efficacy compared to endogenous ligands, leading to a stronger biological response.

- Examples: Examples of agonists include neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine, hormones like adrenaline and insulin, and drugs such as morphine and nicotine.

Antagonists:

An antagonist blocks the action of the agonist. For example Naloxone blocks the action of heroin.

- Binding and Inhibition: Antagonists are molecules that bind to a receptor but do not activate it. Instead, they block the binding of agonists to the receptor, preventing their action. Antagonists can bind reversibly or irreversibly to the receptor.

- Types of Antagonists:

- Competitive Antagonists: Competitive antagonists bind reversibly to the same active site on the receptor as agonists, competing for binding. Increasing the concentration of agonist can overcome the blockade by competitive antagonists.

- Non-competitive Antagonists: Non-competitive antagonists bind to a different site on the receptor than agonists, causing a conformational change in the receptor that reduces its affinity for agonists. This type of antagonism cannot be overcome by increasing agonist concentration.

- Inverse Agonists: Inverse agonists stabilize the inactive conformation of the receptor and induce an effect opposite to that of agonists, leading to a decrease in constitutive receptor activity.

- Examples: Examples of antagonists include beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol) that block beta-adrenergic receptors, antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine) that block histamine receptors, and naloxone, which blocks opioid receptors.

Clinical Applications:

- Agonists and antagonists are used extensively in pharmacotherapy to modulate physiological processes and treat various diseases.

- Agonists are used to enhance or mimic the effects of endogenous signaling molecules, while antagonists are used to inhibit excessive or aberrant signaling.

- Understanding the pharmacological properties of agonists and antagonists is crucial for drug development and therapeutic interventions in conditions such as hypertension, asthma, pain management, and psychiatric disorders.

Conclusion:

In summary, agonists activate receptors and promote cellular responses, while antagonists block receptor activation and inhibit cellular responses. Their interactions with receptors are fundamental to understanding drug actions and designing effective pharmacological interventions.