Transport across the cell membrane is a fundamental process that controls the movement of substances in and out of cells. The cell membrane, also known as the plasma membrane, is a selectively permeable barrier that regulates the passage of molecules and ions. There are two primary mechanisms of transport across the cell membrane: passive transport and active transport.

1. Passive Transport:

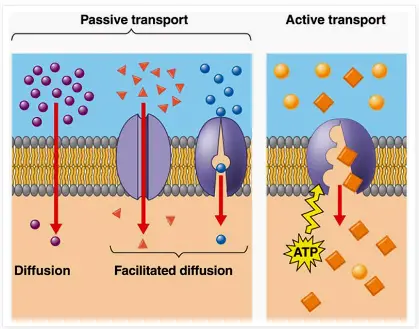

Passive transport does not require energy expenditure by the cell and relies on the inherent kinetic energy of particles. It occurs spontaneously and moves substances down their concentration gradient from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. Passive transport includes three main processes:

a. Simple Diffusion:

In simple diffusion, small, nonpolar molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and lipids can move directly through the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane.

The diffusion rate depends on concentration gradient, temperature, and molecular size.

b. Facilitated Diffusion:

Facilitated diffusion involves the movement of larger or polar molecules that cannot readily pass through the lipid bilayer. This process requires the assistance of transport proteins.

Channel proteins form pores that specific molecules can pass through. Carrier proteins bind to molecules and undergo conformational changes to transport them across the membrane.

c. Osmosis:

Osmosis is the passive movement of water molecules through a selectively permeable membrane, usually via specialized water channels called aquaporins.

Water moves from an area of lower solute concentration (higher water concentration) to an area of higher solute concentration (lower water concentration).

2. Active Transport:

Active transport requires energy (usually in the form of ATP) to move molecules or ions against their concentration gradient from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration. This process allows cells to maintain concentration gradients crucial for various cellular functions. Active transport includes the following mechanisms:

- Primary Active Transport:

Primary active transport directly uses energy, typically ATP, to pump molecules or ions across the membrane against their concentration gradient. The sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ pump) is a well-known example of primary active transport.

In the Na+/K+ pump, sodium ions are actively transported out of the cell while potassium ions are actively transported into the cell, contributing to the maintenance of membrane potential and osmotic balance.

b. Secondary Active Transport (Cotransport):

Secondary active transport relies on the energy stored in an electrochemical gradient created by primary active transport. Two common types are symport and antiport systems.

In symport, molecules are transported in the same direction as the gradient established by primary active transport (e.g., glucose and sodium cotransport in the intestinal cells).

In antiport, molecules are transported in the opposite direction (e.g., sodium-calcium exchange in cardiac muscle cells).

3. Bulk Transport:

Bulk transport mechanisms move large molecules or particles across the cell membrane. There are two primary types:

- Endocytosis:

Endocytosis involves using materials in the cell by enclosing them in vesicles formed from the cell membrane.

Types of endocytosis include phagocytosis (engulfing solid particles), pinocytosis (taking in liquids), and receptor-mediated endocytosis (specific molecule uptake).

b. Exocytosis:

Exocytosis is the opposite of endocytosis, where cells expel substances by packaging them into vesicles and fusing them with the cell membrane, releasing the contents outside the cell.

Exocytosis is essential for producing hormones, neurotransmitters, and other cellular products.

Transport across the cell membrane is a highly regulated process crucial for maintaining cell homeostasis, nutrient uptake, waste removal, and cell communication. The specific mechanisms used by cells depend on the properties of the molecules involved and the energy requirements of the transport process.